Guild Update

COVID and Guild Playtest Meetings

Currently we are allowing playtest facilitators for each location to determine if meetings will be held, as long as they fall within state guidelines. Updates on the status of these meetings will be announced via our BGDG of Utah’s Facebook Group.

Discord and the Guild

The BGDG of Utah’s Discord is a great way to get to know those in the guild and discuss all things game design! If you’ve not joined yet, we’d love to have you come and participate with us!

Online Playtesting Event

Mark your calendars for Saturday, February 27th! We will be holding an online playtesting event that day! We are currently collecting information on who has games they’d like to have played and will be creating an events schedule after collecting that information. If you’ve got a game design in a digital format that you’d like some feedback on then sign up here. Signups will be open until Feb 13th to give us time to create the events schedule.

If your game isn’t quite ready or if you don’t know how to get your game in an online format then you can attend one of Lyle Thatcher’s Design Theater sessions that’s hosted on our BGDG of Utah’s Discord. These have been informative and helpful and might just be the push you need to get your game up and going! Lyle will be posting more information on these either on Discord or in the guild’s Facebook Group.

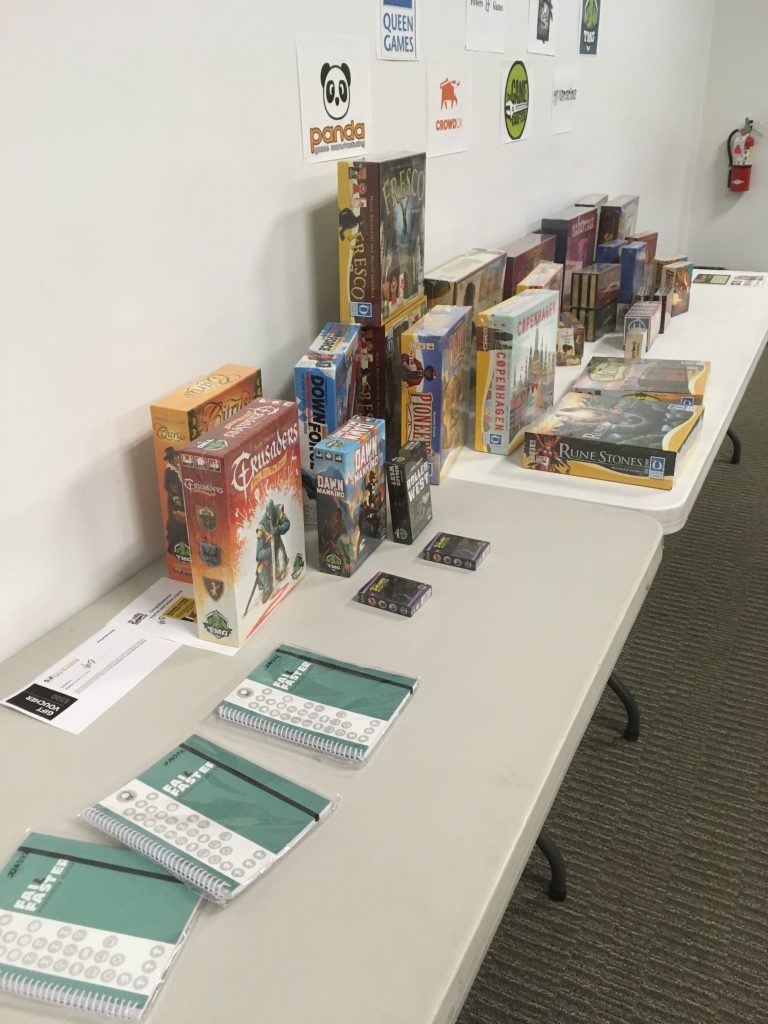

ProtoCON 2022

Just over a year ago the first ProtoCON was held. For those who don’t know much about it, this was an event that was put on by the Events Committee within the guild. It was a bigger success than any of us anticipated it would be and we were so excited to follow up with ProtoCON 2021. Due to obvious events that transpired, this didn’t happen. We have our sights set on ProtoCON 2022. If you’d like to participate in or receive updates on this event then join the ProtoCON Facebook Group! We’ll be looking for designers, playtesters, volunteers and sponsors in the coming months as we prepare for 2022.

BGDG of Utah Social Media

We have an active Twitter and Instagram account now! Please follow and start using #bgdgofutah in your game design related posts and they will be liked, retweeted etc!

Upcoming/Current Events

Recent Game News from the Guild

Here’s BGG’s voting for most anticipated games list for 2021 which will end on Saturday, February 6th! See below for those who are associated with the guild in some way (or on one case, just a friendly local).

Tim Fowers’ Burgle Bros 2, Jeff Beck’s Intrepid, Ryan Laukat’s Now or Never, Jett Ryker’s Dawnshade Justin Potter’s Salt and Sail and Travis Hancock’s Bristol 1350, and though he’s never been a member of the guild he’s a local and so we’ll give a shout out to the artistic talent of Kyle Ferrin with Oath! Take time to vote for all your favorite upcoming games and be sure to give some love to those associated with the guild!

A Documentary

Crafting Arzium is a new documentary that follows Ryan and Mallory Laukat as they design their next game Now or Never.

Some Outside Opinions

Recently Jamey Stegmaier posted on his blog some thoughts regarding Ryan Laukat’s next game, Now or Never, and some responses from the community regarding Ryan’s decision not to use Kickstarter:

Current Design Contests

Two Player Print and Play Game Design Contest (02/14/21 BGG)

54 Card Contest (04/30/21 BGG)

Solo Duo Challenge (05/14/21 The Game Crafter & BGDL)

Ion Award Finalists for 2021

The Ion Award finalists were just announced:

Congratulations to our Finalists in the 2021 Ion Award Board Game Design Competition! (in random order)

Light Category Finalists:

Pauline Kong with Steam Up: A Feast of Dim Sum

Richard Day with Boiling Point!

Dustin Dowdle with Septet

Dan Germain with Singularity Lab

Strategy Category Finalists:

Dave Beck with Distilled

Kate Otte with First Ascent

Stefano Gualeni with Construction BOOM!

Woodrow Arrington with Fates & Favors

Jason Riddell with Dynasty

Guild Related Videos and Reviews

Board Game Workshop Podcast

A Moment of Lightheartedness

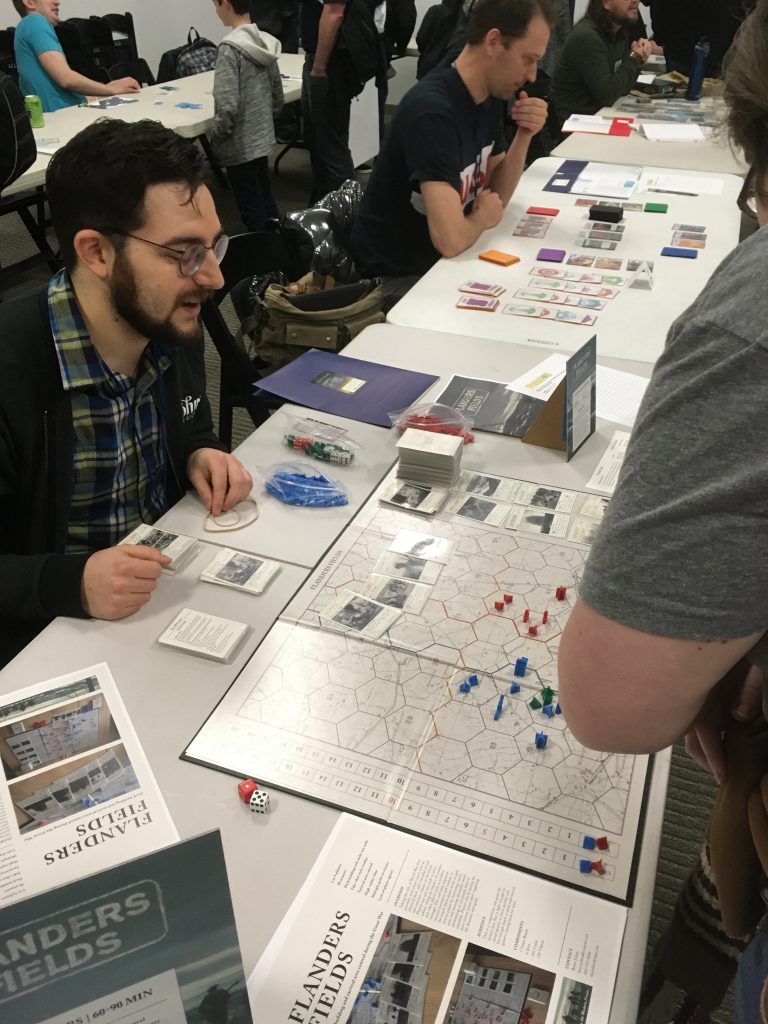

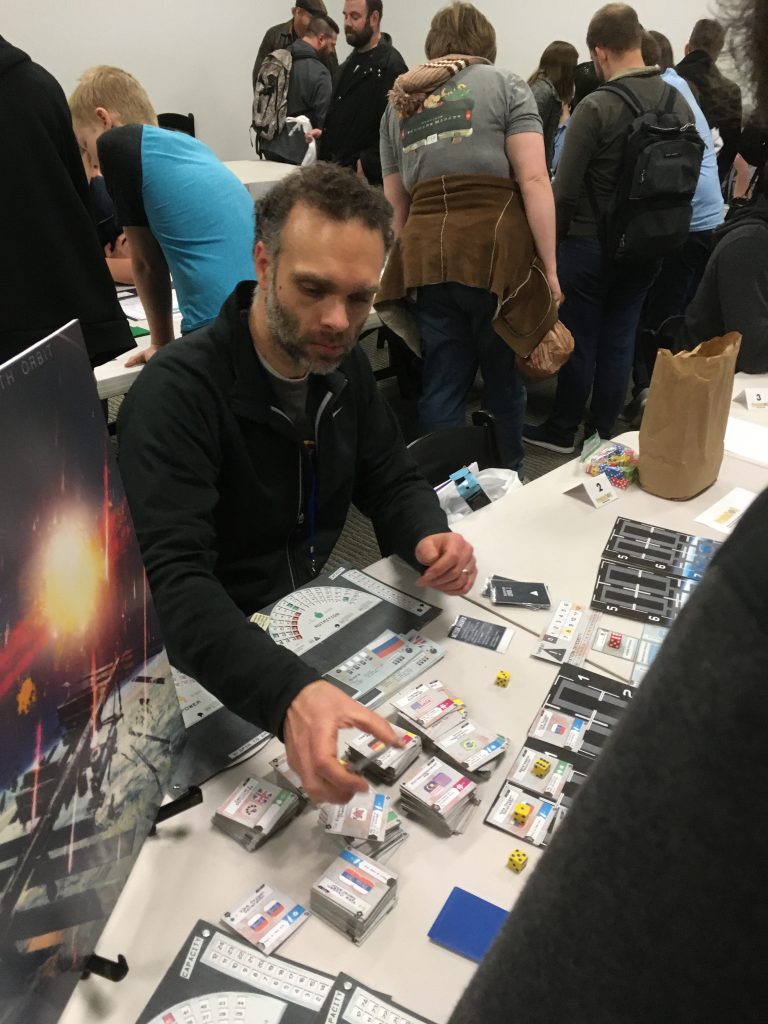

We’ve been seeing Bernie Sanders around the web a bit more lately. It took many of us by surprise that Bernie was actually an attendee at ProtoCON 2020 though! Thanks David Gonsalves for the photos!

Game Design Highlights by Dustin Dowdle

This month we will focus on a few very affordable ways to improve your prototypes. There are hundreds of other ways to do this, and probably better ways to do it as well. I thought I’d post a few of these just to get you thinking of the various ways you might be able to use some simple and affordable techniques.

Opaque Backed Sleeves

Let’s start with the most simple and common idea. Using sleeves with an opaque back will serve two purposes. First, since you are likely using 2.5 x 3.5 paper cards, which you have cut out yourself, these backs will obscure the imperfect cuts and block the see-through paper (some games that matters more than others of course). Secondly, the opaque backing is more sturdy than the common clear sleeves and you can get away with not using an actual card or card-stock as backing, as it’s sturdy enough for a shuffle.

Making Tokens

When making tokens, one of the easiest “chipboard” like substances I have around the house are cereal boxes. These can easily be cut up and used as tokens, as you can see below. By printing out 1″ pics and taping them on the 1″ cereal box cut outs then you’ve got some quick tokens for you game! If you take a little more time then you can always print two of the image and tape them on each side so you don’t see the cereal box… or just tape the image to the colorful side (as you can see I clearly didn’t do that in the center image).

You can take your tokens to the next level with a special kind of Mod Podge called “Dimensional Magic!” This stuff is absolutely amazing! It creates a protective barrier on the tokens and gives them a glossy look. Below you can see I’ve used it on my Marvel Champions and Quacks of Quedlinburg game tokens to provide more durability due to their frequent use. This could also be used on a prototype to give a nice feel and look to tokens if you want that sort of thing.

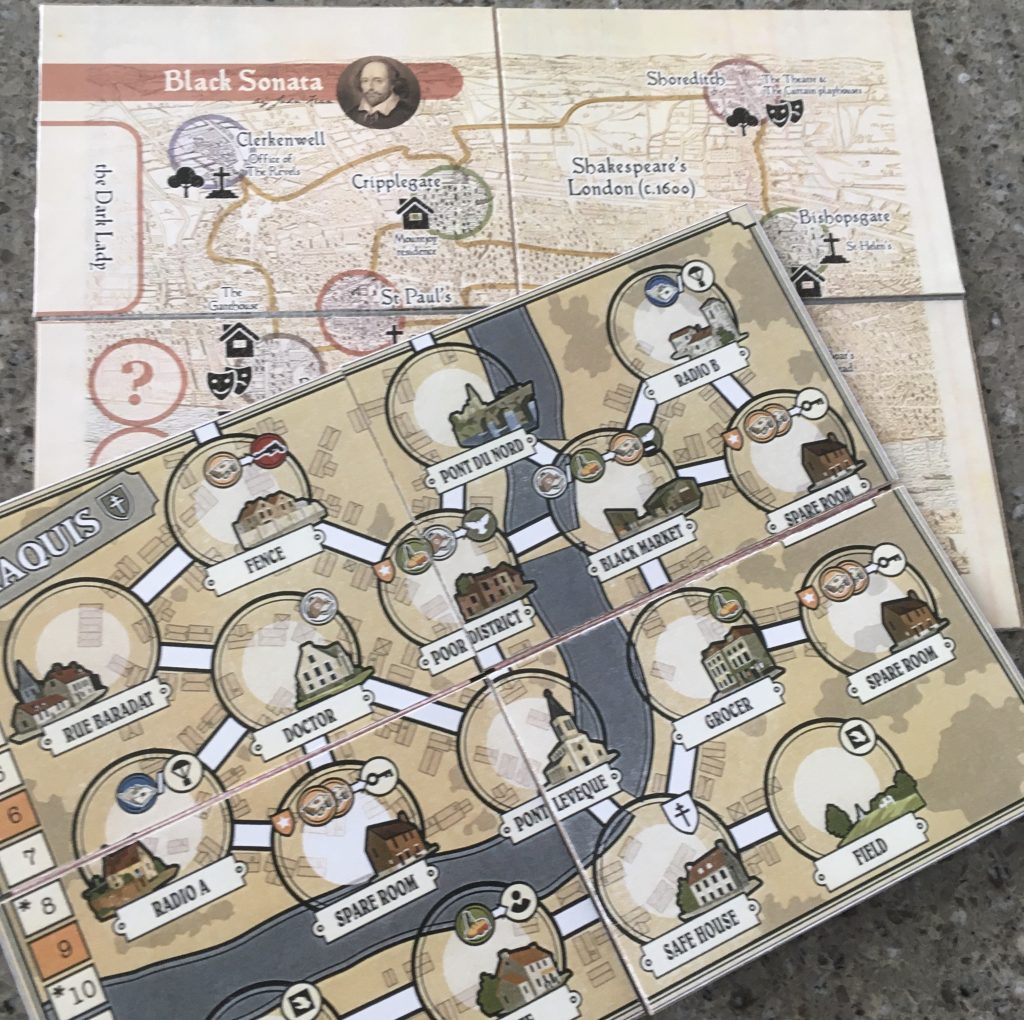

Creating Folding Boards

Below are some PnP folding boards I did for Black Sonata and Maquis. It was as simple as gluing together some pieces of chipboard I got from Amazon (no need to glue it if it’s already thick enough) and use duct tape on the back to hold together the seams. You want to be sure the boards are not taped super close together if the seam bends forward (backward bending doesn’t matter so much) otherwise you won’t have enough clearance to fold the board shut (which is the whole point). Guild member Brandt Brinkerhoff has a video on how to make a folding board that is much more professional looking. If you’re looking for something quick and simple, the duct tape folding board may fit the bill.

Dollar Store Prototyping

Below are pics of things found at the Dollar Store! The hearts will likely be in stock again this month for Valentines Day! They can be used for health tracking and various other things (you get more than I’m showing in the pic). The containers below are one of the best finds though! You get a pack of 10 rectangular or circle shaped containers for $1! Lastly, the colored glitter glue and the 10 empty vials are a dollar each and I was able to use them together for a nice colorful set of potions! Though these were used to geek up my Quacks game, they could easily, and cheaply, be used for a variety of prototypes that may call for that sort of thing!

I’d love to hear about ideas you’ve come up with in the comments below! There are so many ways to add some variety and uniqueness to your projects and it’s fun to see and hear how others are doing things! I look forward to hearing about some of your projects!

Interview with Dwight Adams

Personal Questions

What’s your backstory? Tell us about you and how you got into game design.

My name is Dwight Sheldon Adams. I was born on May 18, 1984 and grew up in North Salt Lake, the youngest of 8 children. I married my wife Ashley in 2008, and I graduated from Weber State University with a degree in Philosophy and English in 2014.

I always enjoyed board games when I was a young child, though all I knew at the time was Monopoly and Life. When I was 13, a friend introduced me to role-playing games. After only a few sessions with him and his brother-in-law, using a set of house rules loosely based on GURPS and D&D, I created my own role-playing system building on theirs. Over the next few years, I played as often as possible with neighbors and friends and wrote a dozen or so supplemental rule sets for the system I’d adopted, including new player classes, spells, monsters, and a few game modules. In my late teens, I found 2nd Edition D&D, which I soon replaced with 3rd Edition. I began transforming a world I’d created for a novel I was writing into a D&D campaign setting, and ended up writing several hundred pages of setting material complete with dozens of classes, feats, spells, monsters, and more than a hundred stat blocks, as well as a few adventures.

By my mid-20s, life circumstances forced me to slow down on D&D. An old role-playing friend of mine suggested I try out some board games with him and some folks at the U of U. At first, I wasn’t particularly enchanted. (to this day, nothing can supplant D&D for me as a time sink) But after playing Bang! and Shadows over Camelot, I was sucked in. I began buying games as quickly as my budget would allow, most of them second-hand or on clearance. Of these, an old beat up version of Chaos in the Old World was probably most responsible for sparking my imagination. Though I don’t tend to focus on area control in my current playing or designing, the variable player powers and the resulting divergent paths to victory awakened me to the fact that board games could provide the same stimulation that make role-playing so engrossing: The companion joys of discovery and problem-solving.

As to how I got started in design, I’ve always been an imitative creator. My love of writing fiction, poetry, and essays and of designing role-playing material and board games are natural outgrowths of my love of the material I consume. At least for me, great works provoke creativity. The sign of a great game is when I feel excited to implement in a new design the mechanics I wish the game had used that it did not. My first foray into board game design was an attempt to create a more interesting role for exposed traitors in Shadows over Camelot. Not long after, I began designing the bare bones of a betrayal-centered game in which betrayer and betrayed had equal say and stake in every decision, pared down to cards alone for the sake of purity. I’ve been tinkering with designs ever since.

Can you walk us through your design process? Do you start with specific themes in mind or want to utilize certain mechanisms?

Oftentimes, my designs are first prompted by the opening visuals of a review for a game that fascinates me. I have a tendency to jump ahead of the reviewer and try to create my own ideas for how elements of the board and other components interact, and if I end up being wrong, BANG–there’s a new idea.

But that’s not enough for an entire game. Instead, I end up with lengthy lists in multiple files on my computer covering interesting mechanics that I’d like to utilize at some point. Some of them are enough to form the core of a game, and I usually jot down some possible secondary mechanics that could complement the core. Some of my fleshed-out game ideas come from taking these sets of coordinated mechanics and contemplating potential themes and how they might influence further design.

If I had to lay out my typical design process, though, I’d say that most often I begin with a gameplay experience that really interests me, often with a general sense of a theme and mechanical core in mind, and then think through possible ways of bringing that experience about. In this effort, I usually try to follow Reiner Knizia’s method of avoiding theme narratively dictating the mechanics but rather letting the experience of play be the central goal of the design. Throughout my design process, I fluctuate my focus between thematic resonance and mechanical cohesion, returning regularly to the question, “Are the changes I’ve implemented contributing to the experience I want to create?”

One interesting product of this process is that one of my games that was originally designed around risk management and market manipulation in stock trading could now be re-skinned as a grand-scale galactic conquest game. Who knew stock trading was such an effective analog to military command?

How did you come to be involved with the guild?

A couple of my friends, Russell Wilkerson and Eric Platt, were regular attendees at Guild meetings for years. They suggested I come, but being unapparently rather shy and self-depracating, I avoided the potential scrutiny. In recent years, I’ve begun transitioning from dabbling to serious design work. Knowing that I’m at my best as a collaborative thinker and creator, I decided it was time to get over myself and come to the Guild. A huge help in this regard was meeting Dustin Dowdle at last year’s SaltCon and Rick Lorenzon at the one before that. Both were very gracious, and Dustin even allowed me to stammer about my current game design for a few minutes without criticism. COVID lockdowns started shortly thereafter, so I had to get my feet wet on Discord rather than in person. I’m really looking forward to meeting as many members as I can in person as soon as it’s practical.

If you could pick 3 games that every designer should have to play, as a sort of game design curriculum, what would you choose?

Chaos in the Old World

Trismegistus

Anachrony

Game Related Questions

You have been working several games, though the main game you’ve been working on is called The Reckoning. Could you tell us more about that?

The main game I’m focusing on right now is The Reckoning. In it, 2-5 players play as leaders of individual sects of a common religion in a medieval fantasy town, vying for their sect to be chosen as the one true faith. To prove themselves, they have to plead for blessings from the gods, satisfying the appetites of the people and spreading their temples and shrines throughout the surrounding rural community. The gods, however, have their own demands. Blessings are granted, but tributes must be paid in rough proportion to favors given. Head priests who fail to repay the gods bring the fury of the gods on the community and the vengeance of the community on themselves.

The gameplay is centered around three main elements:

First, players have to manage three tiers of interdependent workers. Their primary worker type is priests of various skill levels, which can be used to acquire various classes of lesser workers or beg the gods for favors. Lesser workers are used to interact with the community economy through worker spaces. The highest tier worker is each player’s hierophant, which represents the player. The hierophant may be used for any task, but it has the unique ability to offer oblations to a deity in proportion to the amount of worship that deity has received over the round through the actions of the priests.

Second, players have a private area for building their temples and shrines and determining the doctrines that govern their sect. Mechanically, this is a form of engine-building. Each player develops two rows of splayed cards, each of which includes one or more worker spaces and various bonuses for placing workers of certain types in them. Longer rows grant growing chains of bonuses, but rows may be split to give a player small chains with more worker spaces. Doctrines give players unique bonuses, costs, and limitations that diversify them from other players and strengthen their individual strategies.

Third, players must work semi-collaboratively across the central play area, which is broken up into a set of temple cards and a set of market cards. The temple cards represent the unique gifts and demands of each deity. Placing a priest on a card grants a one-time static bonus, but once a card has enough priests on it, the deity’s hunger for worship is satisfied, and all players present receive substantial bonuses and incur greater end-of-game costs for all players, whether they were present on the card or not. The card is removed and replaced, and one or more associated cards in the market area are also removed and replaced. In addition, worker placement in the market area is limited by orthogonal adjacency, so placing a worker in one space opens placement opportunities to one’s opponents.

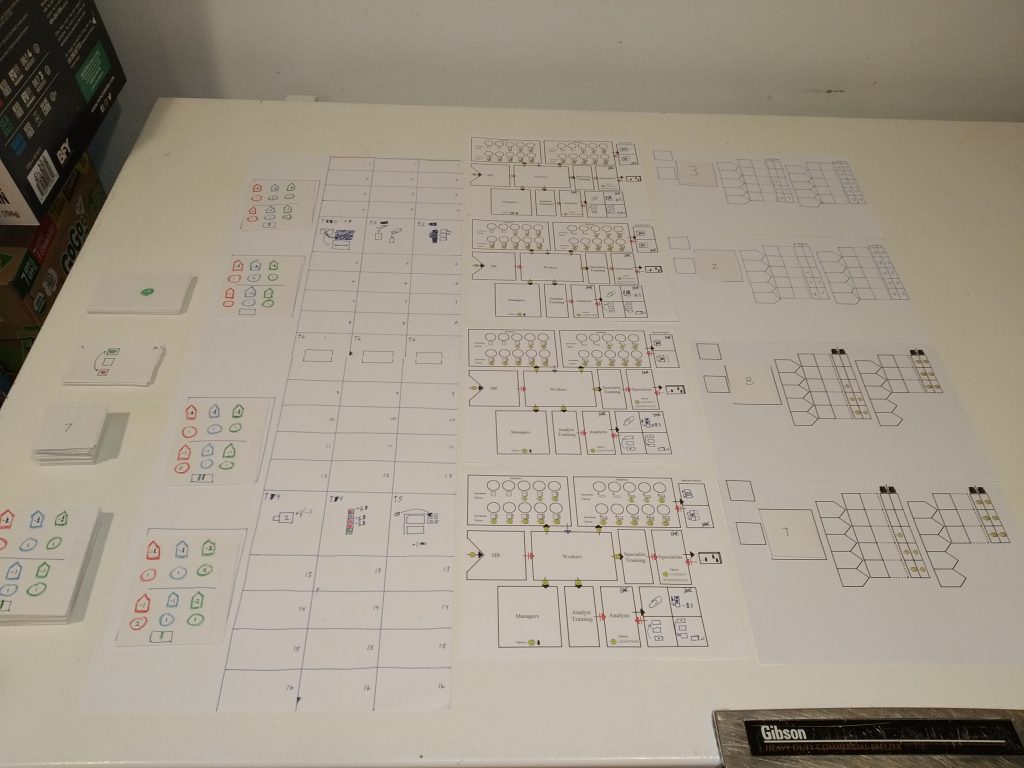

What design challenges did you have to face when designing The Reckoning?

One of the most prominent design challenges I’ve faced with The Reckoning is table space. The original design was sprawling, to say the least. I implemented some major changes to cut down on sprawl, which presented some interesting design challenges: I wanted to preserve the essential features of the original design, such as the temple card-market card interdependence, without making the game too fiddly or restricting player actions too much.

The need to compress play space brought on another challenge: With the game becoming increasingly random due to the reduced number of cards in play, players needed some form of stability for when the game made certain demands of them that couldn’t be satisfied by the available cards. The Reckoning is built on high variability, but it’s at heart supposed to be a Euro experience, so the variability has to present interesting opportunities for strategic play but only mild limitations. The random draw shouldn’t destroy a player’s well-developed strategy. After several design iterations, I settled on private engines and a central player order track with associated worker spaces offering poorer exchange rates for essential resources.

I’ve made many changes to manage these issues, and I’m interested to see how well they’ll work out in playtesting.

Tell us about some of the other designs you’ve been working on.

Another design I’m interested in right now is a token-grid Civilization game. In it, players would begin by drafting one each of three types of advisors: Military, Culture, and Technology. Each advisor would have a series of progressively powerful abilities that can only be triggered if the player’s grid displays the required tokens in the required pattern. Players would use the advisors to gradually add to their board, abstractly representing the way their civilization has developed. The advisors’ more powerful abilities would be difficult to simultaneously achieve, and their most powerful abilities would be mutually exclusive.

In the center of the play area, there would be an additional grid the spaces of which would slowly unlock over the course of the game, allowing increasingly complex patterns. This grid represents the global community, and players can gradually add tokens to it. Players attempt to manipulate the global community to more closely represent their home community, and it’s through this that they achieve global cultural primacy and thereby win.

I also have a game about living with mental illness rolling around in the back of my mind. I recognize that this game would be a major undertaking, as it presents many design and cultural challenges. I’m certainly not informed enough to fairly represent most mental illnesses, so I’d need to meet with experts and sufferers to develop the game’s central theme. I also need to design away from the standard notions of “playing,” “having fun,” and “win or lose.” Players would be tasked with empathizing with sufferers of mental illness through the game’s narrative and mechanics, with a central goal of figuring out what it means to this sufferer to live a worthwhile life, not beating a high score or beating the other players.

Are you hoping to self publish or pitch your designs to a publisher? What are your thoughts behind that?

I’ve mostly been interested in self-publishing. I suppose that in keeping with my shyness, I’d rather engage directly with players than subject my work to a publisher’s scrutiny. My ideal life would be pseudo-Socratic: Let’s meet on the steps of the Parthenon, and I’ll show you my new design in exchange for lunch.

Beyond that, retaining full control of my creative work has always been extremely important to me. On the other hand, I recently read an essay by Michelle Nephew in The Kobold Guide to Board Game Design (a book and essay I’d highly recommend) that went into some detail about what creators can ask of publishers in common contract negotiations, and it made me much more hopeful of retaining creative control even with a publisher.

I also relish the entrepreneurial aspect of self-publishing. It seems like an exciting undertaking, and I’d love to have the direct contact with consumers that I’ve seen in some Kickstarter campaigns.

So I have mixed feelings.

Final Wrap up Questions

How would you suppose the guild could improve to better assist in the game development process?

I’m afraid I don’t have enough experience with the Guild to make any meaningful suggestions. At this point, I believe the onus is on me. I need to participate more–to provide regular updates about my work, read more carefully about others’ work, and so forth. After I’ve engaged more, I may have some ideas for improvement. At this point, the Guild seems very welcoming and encouraging, and that’s all I can ask of it.

If people wanted to contact you or follow your game designs how should they go about that?

I’ve made a facebook page for The Reckoning: https://www.facebook.com/TheReckoningBoardGame/

To contact me, you can reach me on facebook where I’d love to have a few more friends ( https://www.facebook.com/dwights.adams.92 ) or e-mail me at hobbyfuel@gmail.com.

Some really great stuff in this month’s newsletter. I especially appreciate the tips for cheap prototyping – Mod Podge – who knew?!